Learner Qualities

Last week’s blog post examined the importance of learning about learning. In particular, I introduced a model referred to as “the learning pit” that has roots in the work John Nottingham. This week’s post extends the model to explore the nature and purpose of learner qualities.

Learner Qualities: What are they and how do we help learners grow them?

It doesn’t take long to realize that an image of a learning pit is not a “one and done” method for helping people learn about learning. It is one thing to understand the process of learning. It is another thing to understand what attributes make someone effective at navigating the terrain of a learning journey. Left unchecked, many people – young and old alike – are prone to thinking that someone who can play a guitar, read a book, or run a marathon is simply inherently better at these tasks than others. Of course this isn’t true.

As Malcom Gladwell explored in his book, Outliers, the people who are really good at a task – be it playing hockey, programming computers, or singing opera – acquired their strength in each of these domains by learning and practicing and learning again. Gladwell’s studies found that the really great invested at least 10,000 hours in a particular domain. But even this oversimplifies the equation a bit. What makes someone strong at a particular task is the qualities they bring to the learning opportunity, the qualities of being a powerful learner. What are these qualities, and how do we help learners grow them?

There are three models I have found especially useful in working to respond to the questions above. At the Stonesfield School in Auckland, New Zealand (an exemplar of theory-to-practice schooling), the learning culture is constructed around a collection of seven learner qualities: Reflect, Question, Connect, Think, Be Self-Aware, Wonder and Be Determined. The school’s philosophy centers upon helping students thrive in the face of uncertain or complex situations; helping students learn how to learn. School leaders introduce the learner qualities gradually across the course of a school year. Students then monitor their progress around each of the seven learner qualities using progressions (more on this later) during their tenure at the school.

In another model, cognitive scientist, Guy Claxton, refers to learner qualities as “the elements of learning power” (p. 107, 2018). In Claxton’s model, the essential attributes are Curiosity, Attention, Determination, Imagination, Thinking, Socializing, Reflection, and Organization. Claxton believes the best thing we can do for students is to teach learners to teach themselves. His “Learning Power Approach” aims to build in all students the confidence and capacities of being a good learner so they can be successful, individually and collaboratively, in school and beyond (p. 40, 2018).

Finally, Frey, Fisher, and Hattie’s (2018) research directs attention to the importance of developing “assessment capable” learners. This descriptor does not intend to convey that students perform well on assessments, but rather that learners are capable of assessing their own progress toward particular learning goals; capable of identifying what they have done well and where they need more work or extra help.

No matter which framework you select, it is important for learners to understand that there are specific qualities that lead to more efficient and effective learning. More important yet, it is essential that they understand how to grow these capacities within themselves. As teachers, parents, and/or coaches there are four distinct but interdependent ways we can accomplish this: 1. Explicit instruction, 2. Progressions, 3. Liberated Learning, and 4. Metacognitive Reflection.

Explicit Instruction

While children are by nature learners, the dispositions of learning will not necessarily cultivate themselves. Educators are advised to design learning opportunities – interventions – that explicitly focus on each of the learner qualities. Such opportunities challenge students to examine the nature, value, and purpose of a learner quality as applied to a learning task. For example, if students are challenged to build the tallest standing structure they can using a limited set of resources, they can later reflect on the role determination played on their progress. Then, in the future, they can extend that shared experience and resultant reflection to think about how determination will impact their ability to complete a science investigation, run a mile, or read a challenging book.

Progressions

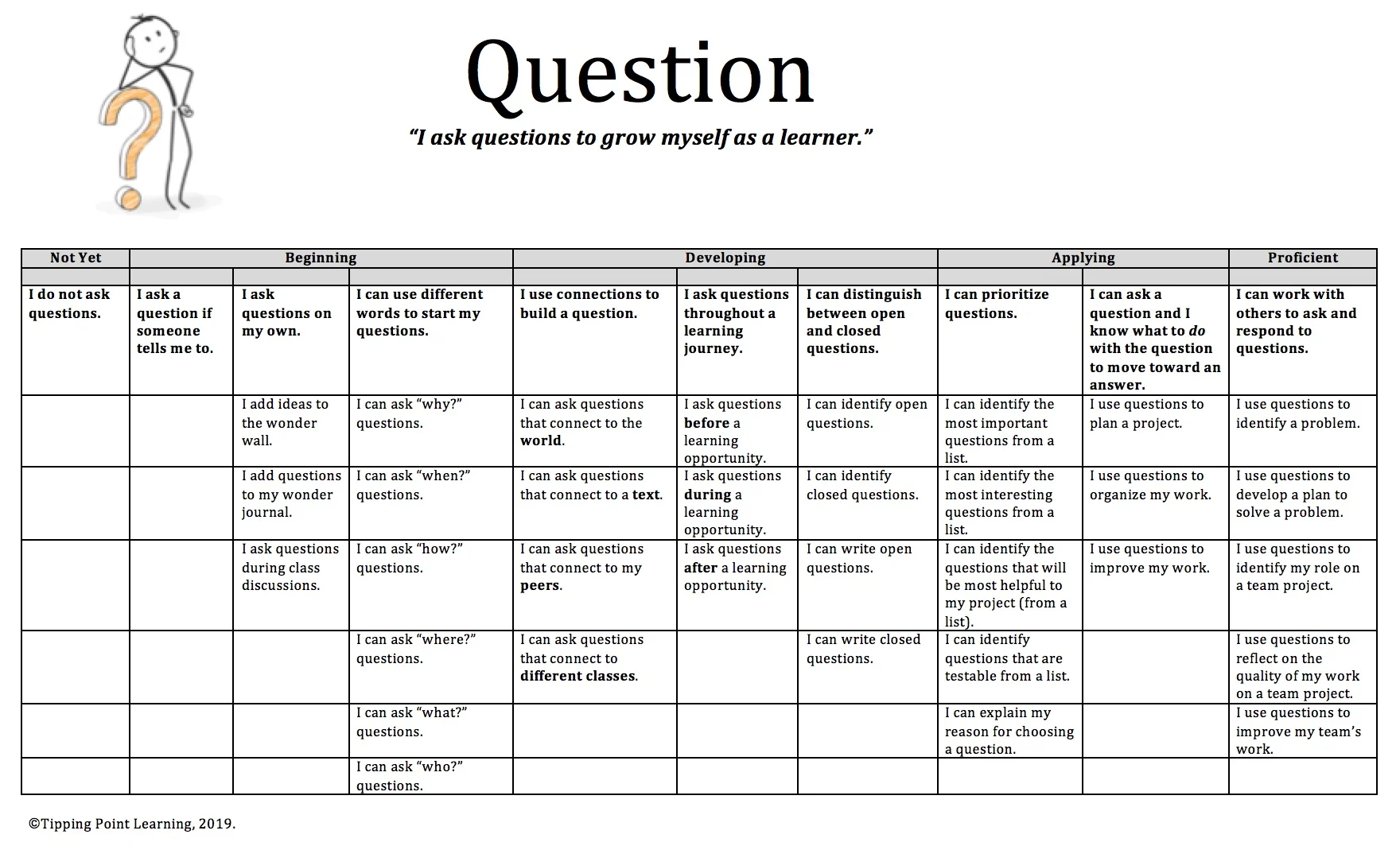

Progressions are tools developed to assist students in monitoring their own growth toward a learning goal. In effect, they are tools designed to foster the development of assessment capable learners. As mentioned above, school leaders at the Stonesfield School in New Zealand developed a set of progressions (rubrics) to help students monitor their progress around each of the seven learner qualities the school curriculum is grounded on. Each progression spans an estimated ten to twelve years of development. At Stonesfield, the final destination is “part of me” status which intends to convey that an attribute is so engrained in a learner it is actually a part of their being. An example of a progression for the learner quality “Question” is included below.

Liberated Learning

One of the most important and often overlooked components of learner quality development is providing students time, space, and opportunity to define and work toward their own learning goals. I have come to call this liberated learning. The soccer player who wants to improve her shot, the fourth grader who wants to learn how to repair his bike, the sixth grader who wants to learn how to make a stained glass window. Allowing students to engage in tasks that are interesting and useful to them draws upon and develops learner qualities more robustly than didactic tasks can accomplish on their own. Whether Passion Projects, Breakthrough, Genius Hour, or simply working on a project in the backyard, liberated learning allows students to practice learner qualities on tasks that are inherently meaningful to them.

Metacognitive Reflection

Finally, it is important to challenge learners to explicitly reflect on when, where, why, and how a specific learner quality served a particular purpose on a learning journey. This action fosters metacognitive awareness in students – and ourselves -- that can be applied to future learning endeavors.

Summary

We cannot know what the future holds or which personal or academic skills will be of most value to our youth down the road. This makes it less important for students to master content (“knowing”) and more important for them to master learning. Rest assured, learner qualities do not get in the way of academic or athletic standards. Instead, they are the foundation on which all learning is built.

As you continue through the next week, quarter, trimester, or season, ask yourself and the learners around you:

What are the qualities that make a strong learner?

How do I grow these qualities in myself?

How do I grow these qualities in others?

Citations:

Claxton, G. (2018). The learning power approach: Teaching learners to teach themselves. Thousand Oakes, CA: SAGE.

Frey, N., Fisher, D., & Hattie, J. (2018). Developing “Assessment Capable” Learners. Educational Leadership. 75(5), 46 – 51.

Gladwell, M. (2008). Outliers: The story of success. NY: Little, Brown, and Company.

Stonesfield School. Retrieved from: https://www.stonefields.school.nz/